Home Curriulum Vitae Research Fun stuff Contact

What does tracking look like?

Uploaded 23-01-2020.

Tracking is done "[...] explicitly by forming groups of students through selection [...], with the aim of serving students according to their academic potential and/or interests in specific programmes." (OECD, 2005, p. 84) How many groups of pupils are formed, when pupils are placed in these groups, how pupils are allocated, and in what way the groups differ varies a lot between countries. Below I discuss how countries differ on the following dimensions of a tracked system:

- Age of first selection, or "early" tracking

- Number of tracks

- Vocational orientation and vocational specificity

- Length of the tracked system

- Manner of selection into tracks

- Between school or within school tracking

- Track mobility

- Index of multiple measures

Age of first selection, or "early" tracking

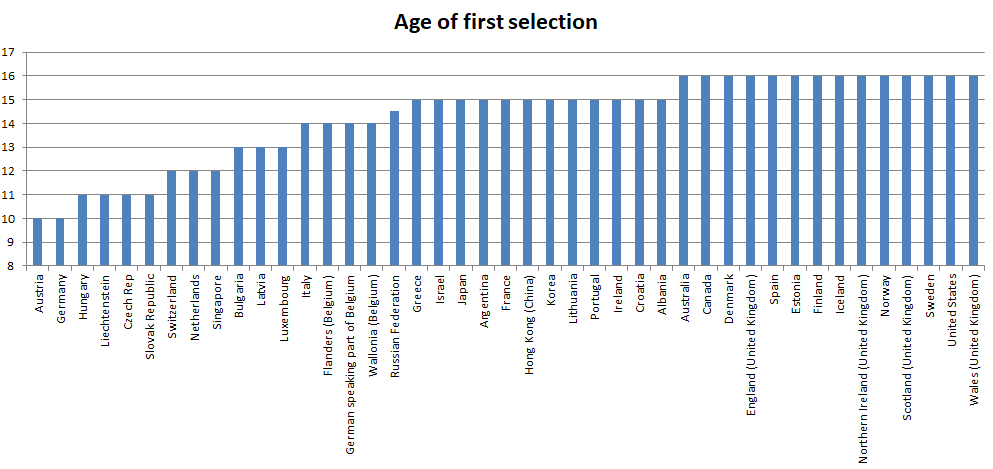

The age at which children are selected into tracks for the first time is considered to be a tracked system's most important aspect as well as its most controversial one. The figure below shows for a selection of countries the age at which the first selection is made. In some countries children are divided into tracks at the age of 10 (Germany and Austria), while in other countries children are tracked later, for instance at the age of 16 (Sweden and the US). The current age of the first selection varies between 10 and 16.Figure 1 (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Data is based upon a consensus of Eurydice (2018), OECD (2016), OECD (2010), OECD (2007), OECD (2005), OECD (2004).

Source: Data is based upon a consensus of Eurydice (2018), OECD (2016), OECD (2010), OECD (2007), OECD (2005), OECD (2004).

Often it is not the age of first selection that is used in academic literature as a measurement for tracking, but one chooses to use a dichotomous measure derived from the age of first selection: early tracking. Researchers thus divide the available countries into early and late trackers. There are two main reasons for using this measurement. First, tracking is expected to have a (particularly) negative effect if selection into tracks is done "early on" (See also the post Theoretical expectations - Too early?). However, what constitutes as "early" tracking or what age would be considered a good one is unclear (theoretically and empirically) and potentially depends on the educational systems' other characteristics. Second, having only two groups of countries (early vs late trackers) facilitates drawing comparisons and estimating the effects of tracking: Researchers only needs to compare two groups instead of multiple ones.

As discussed above "early" is a relative notion, and in the academic literature there is no standard "early" as to the first time of selection. Most studies using the cross-sectional data of PISA or TIMSS to study tracking, will consider tracking to be early if pupils are tracked before the tests are held. Therefore, in the case of PISA, which tests pupils at the age of 15, tracking is considered "early" if pupils are selected before that, while in the case of TIMSS, which tests pupils at the age of 14, this would be before the age of 14 (e.g. H&M, 2006). Other researchers will use various definitions of "early" in order to show that the estimated effects do not change too much due to arbitrary decisions on the definition of "early" made by the researchers or even that the estimated effects become more marked if tracking is done earlier.

Papers that use this definition: H&W (2006); Korthals (2015).

Back to top of page

Number of tracks at a specific age or grade

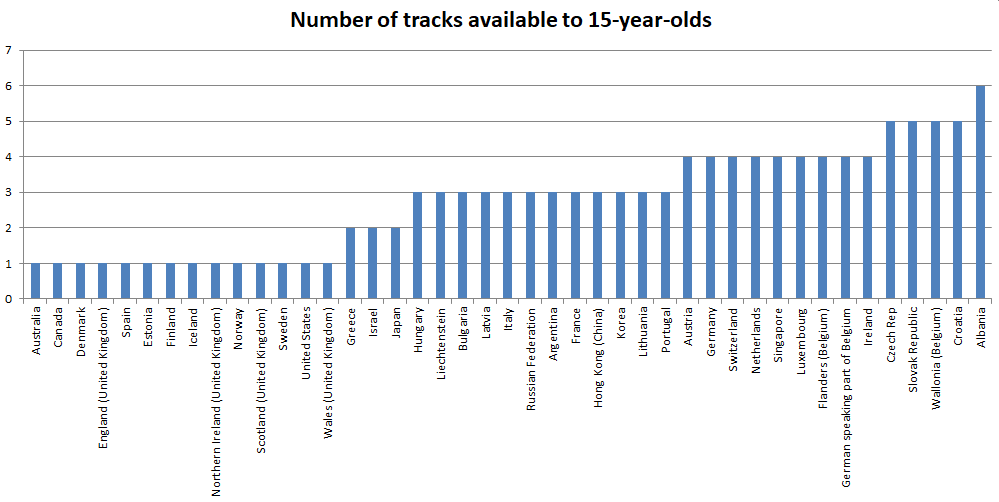

After the age of first selection, a tracked system's second most important aspect is the number of tracks available to pupils at a specific age or grade. Tracking divides pupils into different educational programs according to their academic potential and/or interests. Tracking often sorts pupils into more academic and more vocationally oriented tracks. However, there may even be more than two tracks. Figure 2 shows, for a selection of countries, the number of tracks available to 15-year old pupils.Figure 2 (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Data is based upon a consensus of Eurydice (2018), OECD (2016), OECD (2010), OECD (2007), OECD (2005), OECD (2004).

Source: Data is based upon a consensus of Eurydice (2018), OECD (2016), OECD (2010), OECD (2007), OECD (2005), OECD (2004).

Counting the number of tracks in a country at a specific age or grade is often not straightforward. In each country, the institutional setting is frequently quite specific and is not easily captured in measurements which capture the same concept across nations. For instance, in the Netherlands the two vocational tracks vmbo-gemengd en vmbo-theoretisch are often considered to be one track in everyday school practice. Pupils in both tracks take the same central exit exams. and often pupils in both tracks are in the same class, yet those in vmbo-gemengd have one theoretical course less and instead take one vocational course. So, should these tracks be regarded as two tracks when describing the Dutch tracking system? The use of special needs education is often not considered a form of tracking and is therefore also not included here.

There are similar difficulties in using the number of tracks in a research design. Even though the number of tracks between countries might be the same, the group of pupils selected into them may differ widely. Consider for instance a country that has two tracks and selects twenty percent of its lowest achievers into a track, as opposed to a country that selects twenty percent of its highest achievers into a track. Although both countries have two tracks, the effects of having two tracks on pupil outcomes might be very different.

Similar to the further specification of the age of first selection into early tracking, the measurement of "the number of tracks available to pupils" may be further specified as a "great number of tracks available to pupils". In general, it is thought that the more tracks there are, the more homogeneous the pupils within a track will be, and the more the education is differentiated between tracks. Following this, the more tracks there are, the larger the expected effects of tracking should be (See also the post Theoretical expectations- Peers & Teaching).

Papers that use this definition: Korthals & Dronkers, 2015; Horn (2009).

Back to top of page

Vocational orientation and vocational specificity

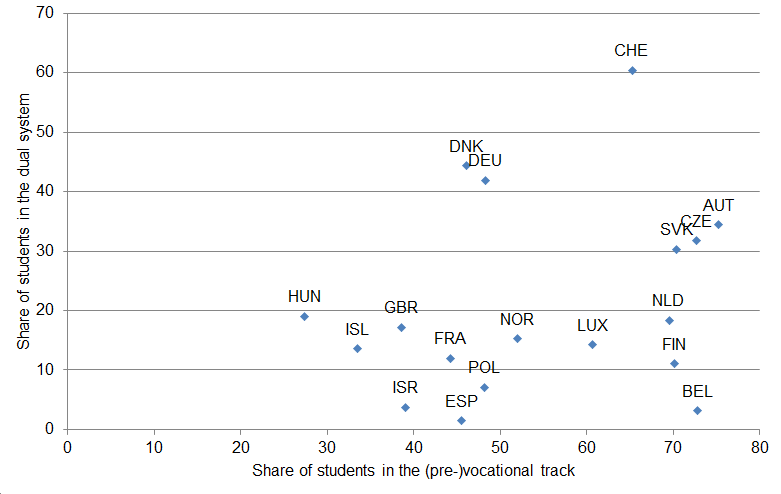

Tracking countries often offer tracks that are more academically or vocationally oriented. The more pupils there are in vocational education, the greater the system's vocational orientation of the system will be. A system's vocational orientation is therefore often measured by the percentage of pupils found in a vocational program.It is thought that if there is only a small percentage of pupils in the vocational program the more, they are considered to be "less": less smart, less able, less motivated, et cetera. So, a small percentage of pupils in the vocational track would therefore increase the stigmatizing effect (See also the post Theoretical expectations- Stigma).

The vocational specificity is a measure describing the degree to which the pupils' vocational training takes places within a workplace, and therefore the degree to which is called a dual system. It is considered very positive for pupils to learn vocational skills in the workplace, as it is then more likely that a pupil will learn skills that the job market demands (See also the post a href="theory">Theoretical expectations - vocational profession and dual systems). Most dual systems are only found in upper secondary schools. Vocational specificity is measured by the percentage of pupils in upper secondary school that are taught in the dual system.

The figure below shows for a selection of countries both the system's vocational orientation and vocational specificity are shown. It can be seen that the two measurements are not closely related: countries with a high vocational orientation do not automatically also have a high degree of vocational specificity.

Figure 3: The vocational orientation (horizontal axis) and the vocational specificity (vertical axis) for a selection of countries (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Data is taken from OECD (2014).

Source: Data is taken from OECD (2014).

Notes: Only countries that have a (pre-)vocational track and within the vocational track a dual system.

Papers that use this definition: Horn (2009).

Back to top of page

Length of the tracked system

A measure related to the age of first selection is the length of the tracked system, or the amount of time spent in tracks within the compulsory schooling system. If all countries would start and end their compulsory schooling at the same time, this measurement would reveal identical patterns to those at the age of the first selection. However, compulsory schooling starts and ends at different ages in different countries, so the length of a tracked system is one of the dimensions along which tracking differs across countries.Papers that use this definition: Ariga & Brunello (2007)

Back to top of page

Manner of selection into tracks

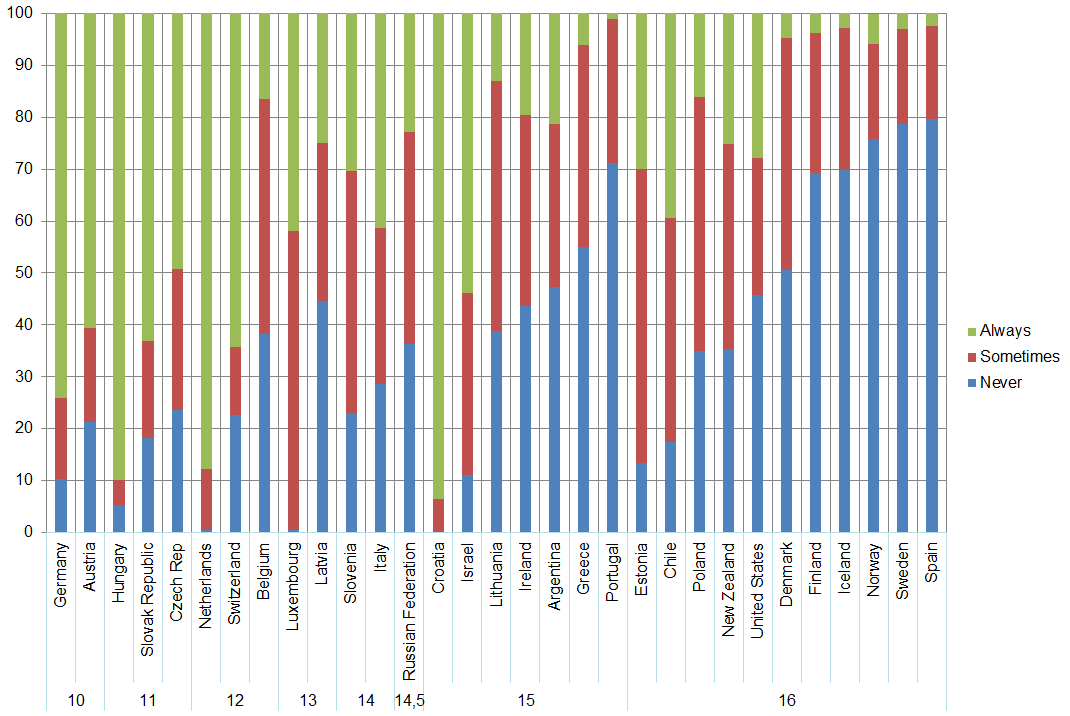

Most tracked systems provide multiple tracks for their pupils, with different ability levels. Pupils are sorted into these tracks and the implicit idea is that this sorting is based on ability. So, within the allocated track, each pupil will receive the education that matches his/her ability level. However, not all countries actually sort their pupils into ability-based tracks. In certain German states for instance, pupils are free to choose their own track.Only rarely is there any data collected on the manner of track allocation. In PISA, school principals are asked if, in accepting pupils to the school, they take into account prior performance either never, sometimes or always. In Korthals & Dronkers (2016), the answers to these questions were used to indicate whether pupils had been allocated into tracks on the basis of performance (a proxy for ability). Figure 4 shows per age of first selection and per country, the percentage of schools which either never, sometimes or always take into account prior performance in accepting pupils to the school. The figure shows that the later a country selects pupils into tracks, the less likely this is done on the basis of a performance measurement.

Figure 4: The percentage of schools per country that either never, sometimes or always take into account prior performance in accepting pupils to the school, and the age of first selection (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Data is taken from Korthals & Dronkers (2016).

Source: Data is taken from Korthals & Dronkers (2016).

Papers that use this definition: Korthals & Dronkers, 2016.

Back to top of page

Between school or within school tracking

In most tracking countries pupils who follow different tracks also go to different schools or school buildings. However, this is not the case for all countries. For instance, in the Netherlands some schools offer multiple tracks within a single school building.In countries where pupils from different tracks attend the same school, more interaction between pupils in different tracks is likely. This might reduce both the stigmatizing effect as well as the differences in civic skills between pupils from different tracks (See also the posts Theoretical expectations - Peers & Stigma). However, since the pupils do not attend the same lessons, this interaction will still be limited.

Papers that use this definition: I am not aware of any papers scrutinizing the differences in effects between and within school tracking on pupil outcomes.

Back to top of page

The degree of track mobility

If pupils are placed into tracks based on some sort of ability measure, this is usually based on the pupil's performance at that point in time. It could however also be possible that the pupil's "true" academic potential or ability is only revealed after he/she has been selected into a track. For instance, because selection is done at a too early age when it is rather difficult to measure academic potential (See also the post Theoretical expectations- Too early?). In a "flexible" tracked system, it would be possible for a pupil to move between tracks if it turns out that he/she is in a wrong track. Track mobility could be a way of setting right any initial allocation mistakes. Yet not in all tracking countries is it possible to move between tracks, or maybe only by moving into a lower track. Whether track mobility is indeed a possibility and to what degree this actually happens, is also a measure of a tracked system.Papers that use this definition: I am not aware of any data sources which contain data across nations on track mobility or of any papers looking into the cross-country effects of the possibility (or the degree) of track mobility on pupil outcomes. A related work is Jacob and Tieben (2009), which compares the use of track mobility between German and Dutch pupils from different social backgrounds.

Back to top of page

Index of multiple measures

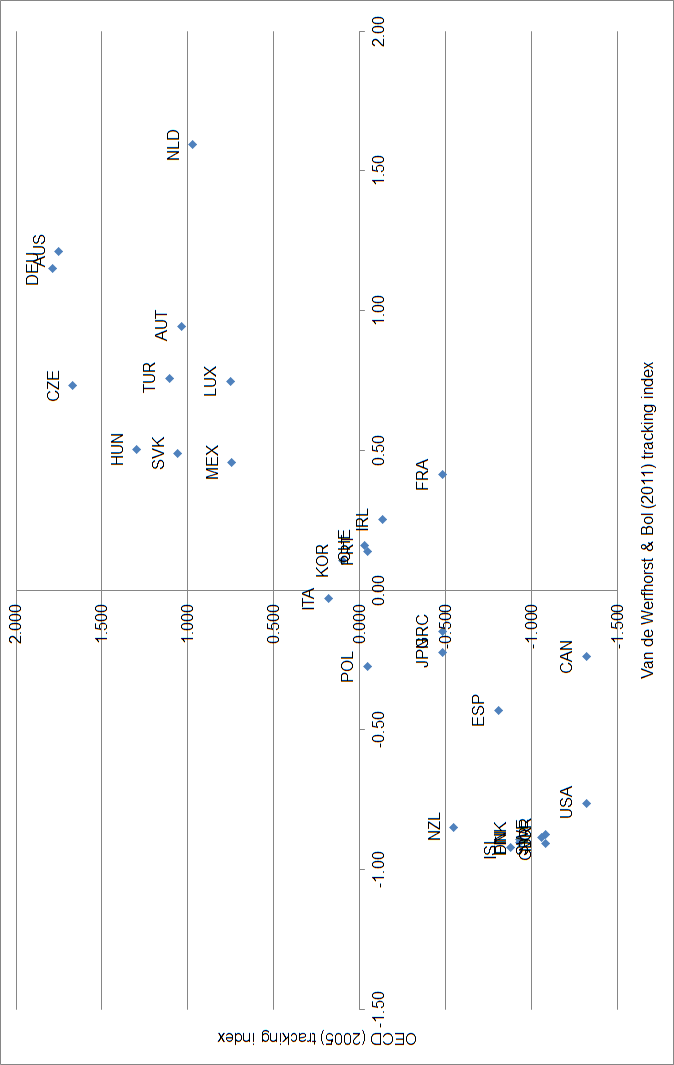

Often the different tracking characteristics described above are related. Sometimes this is true by definition: a country that only selects its pupils after the age of 16, will as a consequence have only one track for pupils aged 15. In order to account for multiple tracking measures simultaneously, some researchers have chosen to combine all of the different measurements in an index. For instance, the OECD (2005) combined the age of first selection, the number of tracks available to 15-year-olds, the proportion of 15-year-olds enrolled into programs providing either access to vocational studies at the next program level or direct access to the labor market, together with some broader measures meant to capture a system's stratification (the proportion of 'repeaters' among 15-year-olds, the total variance in pupil performance, the total variance in pupil performance between schools, and the percentage of variance in pupil performance explained by ESCS). Also Van de Werfhorst & Bol (2011) have constructed a tracking index. Theirs is a combination of the age of first selection provided by OECD (2005), the duration of the tracked system and the OECD's number of tracks at the age of 15 (2005).Figure 4 shows these two examples in one figure for a selection of countries. The two indices displayed here are closely related. Since both are in part based on the same data, this is not surprising. However, it is also exemplary of how related the different tracking measurements are. For instance, looking at the countries with a great number of tracks available to 15-year-olds it can be seen that these countries often also have an early first selection. The age of first selection and the number of tracks seem to go hand in hand. This relatedness makes it very difficult to isolate the effect of the age of first selection from the effect of the number of tracks.

Figure 5: Tracking indices from the OECD (2005; horizontal axis) and Van der Werfhorst & Bol (2011; vertical axis) (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Data is taken from OECD (2005) and Van der Werfhorst & Bol (2011).

Source: Data is taken from OECD (2005) and Van der Werfhorst & Bol (2011).

The measure's scale is uninformative in itself. The multiple measures that these indices combine are not all on the same scale: for instance, the age of first selection is the age in years, while the vocational orientation is a percentage. Combining these two measures would not make any sense, which is why indices are often combined using statistical methods like factor analyses in order to distill the part of the variations between the measurements they have in common.

Papers that use this definition: Van de Werfhorst & Bol (2011).

Back to top of page

References: pdf

Orginially uploaded on 27-12-2019. On 23-01-2020 a new version was uploaded with minor changes in the references and the title of the y-axis of Figure 5 was adjusted.