Home Curriulum Vitae Research Fun stuff Contact

Does tracking matter for performance?

Uploaded 23-01-2020.

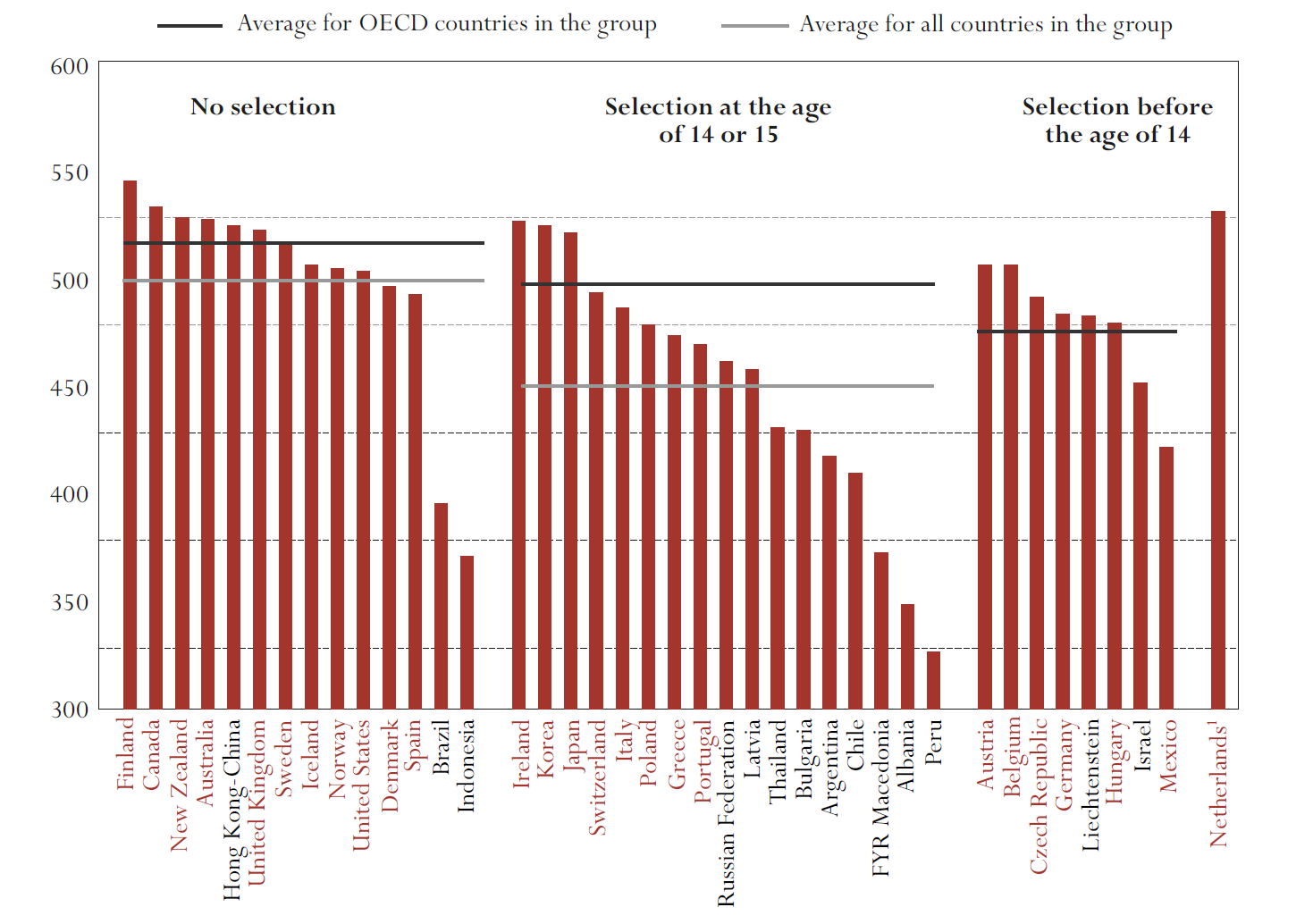

Tracking has a bad reputation and this mainly comes from the hypothesis that tracking causes unequal opportunities between groups of pupils. In addition, it is often thought that this increase in inequality is not even "compensated" by higher average performance and therefore tracking has no benefits whatsoever. But is this the case? Figure 1 below comes from an OECD publication based on the PISA 2000 test scores in reading (OECD, 2005). This figure suggest that countries that select before 15 or before 14 perform on average worse than countries that do not select. This would mean that the assumed increase in inequality goes along with even a decrease in performance!

Figure 1: Average test scores in reading by age of selection. (click on image to enlarge)

Source: OECD (2005; Figure 4.6).

Source: OECD (2005; Figure 4.6).

However, when we look over time at the performance of pupils in a constant sample of OECD countries who have participated in PISA, we see a different picture. The three figures below show the average PISA test scores in reading, mathematics and science for the years 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2012 for countries with and without selection before 15. These figures show that for reading and science (at least in the early years) there is no difference between countries that select before 15 and countries that do not: the confidence intervals (shown by the grey areas) overlap between the early and the late trackers. For mathematics scores, the early tracking countries score higher. We do not really see a time trend in PISA, maybe slightly for science in favor for the early trackers.

Figure 2: Average PISA test scores over the years 2000-2015 for early (blue line) and late tracking countries (red line). (click on image to enlarge)

(A)

Notes: Constant sample of 27 countries. Early trackers are the 9 countries that track before the age of 15: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Switzerland.

Based on simple comparisons like these it is very difficult to draw conclusions on the effects of tracking since other differences between countries (differences that potentially are related to whether or not a country tracks early!) are not taken into account. To put it simple: Correlation is no causation! This leads us to look at the scientific literature that tries to go beyond correlation and tries to estimate the causal effects of tracking.

Does tracking really matter? Or: What are the casual effects of tracking?

The effects of tracking on cognitive outcomes (pupil performance) are not well-known, even though the number of studies into tracking is increasing every year. Positive, insignificant, and negative effects of formal tracking on pupil performance are. Due to the inherent differences in cross country comparisons, there are only a small number of causal studies into the effects of tracking. I will go into this literature below. There are much more correlational studies, of which some I will mention here, but only briefly. To fully understand why these correlational studies might provide incorrect evidence I refer to the blog post How to study tracking?.Differences-in-differences studies using elementary and secondary school tests

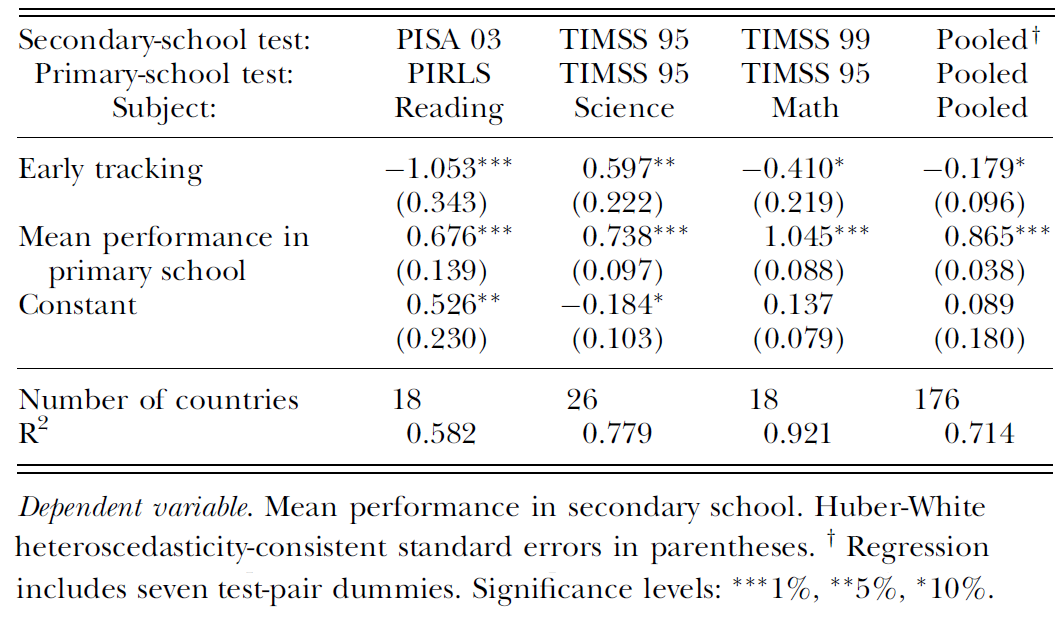

The most influential paper in the (economic and sociological) tracking literature is probably Hanushek & Woessmann (2006; HW2006) and for this reason I will discuss this study somewhat extensively. These authors introduced the Differences-in-differences design using elementary and secondary school youth tests that is copied in many more studies with a slightly different focus (e.g. Ruhose & Schwertz, 2016 which looks at the migrant-achievement gap or Koerselman, 2013, which looks at incentive effects before tracking). HW2006 use the fact that in modern western countries no country selects pupils into tracks in elementary school, while a lot have done so by the age of 15. These age groups are exactly the age groups which international tests target. PIRLS/TIMSS targets elementary school pupils at the age of 10 and PISA/TIMSS targets secondary school pupils at the age of 14/15. The authors argue that the (only!) systematic difference between the group of countries that selects pupils into tracks between 10 and 14/15 and those countries that do not is this selection into tracks. By looking at the two groups of countries before and after one groups tracks pupils, they can estimate the causal effect of tracking. Naturally there are some limitations to this study and the causal claims, but given the difficulty in studying cross country differences this method is very convincing.Unfortunately, the results of HW2006 are not super clear cut on the effects of tracking on pupil performance. Below an adjusted version of their main table is shown. For the three different topics of the youth tests (reading, mathematics and science) the table shows separate results and the pooled results (combining tests on all topics). To make the table a bit more manageable I have only included the most "extreme" results. For reading the authors find a consistent pattern that early tracking (before 14 or 15) leads to lower performance. For science the authors find some evidence for a positive effect (as the table below shows), but this effect is not very consistent across samples. For mathematics the authors find negative effects, like with reading, but these are never (very) significant. Or: It could just as well be that there is no effect of tracking on mathematics performance. The pooled model (last column in table below) shows a negative effect, but also this is not very significant. The authors conclude "... there is [...] a tendency for early tracking to decrease performance".

Figure 3: Regression coefficients on the effects of early tracking on mean performance. (click on image to enlarge)

Source: H&W (2006; part of Figure 4).

Source: H&W (2006; part of Figure 4).

As said before, the method of HW2006 is often used by other authors to look at different aspects related to tracking. But there were also criticisms on the method of HW2006. For instance, the number of observations used is very low (between 18 and 176) and some pupils have only been tracked for a (very) short period when they took the secondary schools tests and thus tracking had no time to change performance.

The most severe critique came from Jakubowski (2008), who tried different ways of specifying the HW2006 model, making the different tests more comparable, and used different samples. Jakubowksi (2008) concludes "... that tracking was confounded with the effect of policies common in [ed: post-communist] Eastern Europe and there is no evidence in international data for the negative impact of tracking in other countries.".

Instrumental variable approaches

Another method to obtain causal estimates is to use instrumental variable (IV) analyses. I refer to the blog post How to study tracking? for the technical details. For now: IV can be a very convincing method to be able to make causal claims, but the assumptions are really (!) strong and they cannot be fully tested and thus the reader has to mostly just "trust" the authors. In a good IV study the authors will put a lot of effort in to convince the readers that these strong assumptions hold, but since these can never be tested not all readers might be convinced.One IV study into the effects of tracking is Ariga & Brunello (2007). The authors look at the length of the time in school spend separated and find positive effects of spending more time tracked. Ariga & Brunello (2007) find that "... one additional year spent in a track raises average performance by 3.3 to 3.4 percentage points ...". These results therefore contradict the results of HW2006, if we take their conclusion of a tendency of a the negative effect of early tracking.

Please see also the blog post What does tracking look like? for a discussion on how using the time spend in school tracked differs from other ways to measure tracking.

Also I have worked on a study using IV to estimate the effects of tracking on performance (Korthals, 2016). I find a "... a consistent positive effect between the level of differentiation and pupil performance.". However, I am not convincing able to show evidence that the strong assumptions that are needed in IV analyses hold, which casts doubt on the causal claims of these results.

No within country studies?

I prefer to discuss here only cross country studies, since I believe tracking as a general phenomenon is best (only?) fully captured in a cross country study. Within-country-studies that look at tracking reforms or use other within country variation, are often dependent on very country specific aspects or have difficulty separating out many changes which happen all at once (for instance, curriculum changes from tracking changes). However, within country studies provide often much better settings to study causal effects, which makes them nonetheless very valuable to understand aspects of tracking. I will discuss this literature later in this post, so keep reading ;).What could also be the case

There are other potential explanations, besides tracking, for test differences between early and late tracking countries. Countries differ on numerous aspects from each other. In studying tracking, all these other differences are often (adequately) controlled for at the country level. However, if the group of countries that track early, differ in more ways than just tracking from the group of countries that tracks their pupils late, multiple effects could be intertwined.Below I will discuss two examples of this, namely motivation differences between groups of countries that track early and that track late and anticipation effects in early tracking countries. These could be other reasons why it is difficult to estimate the effects of tracking.

Motivation differences in international tests

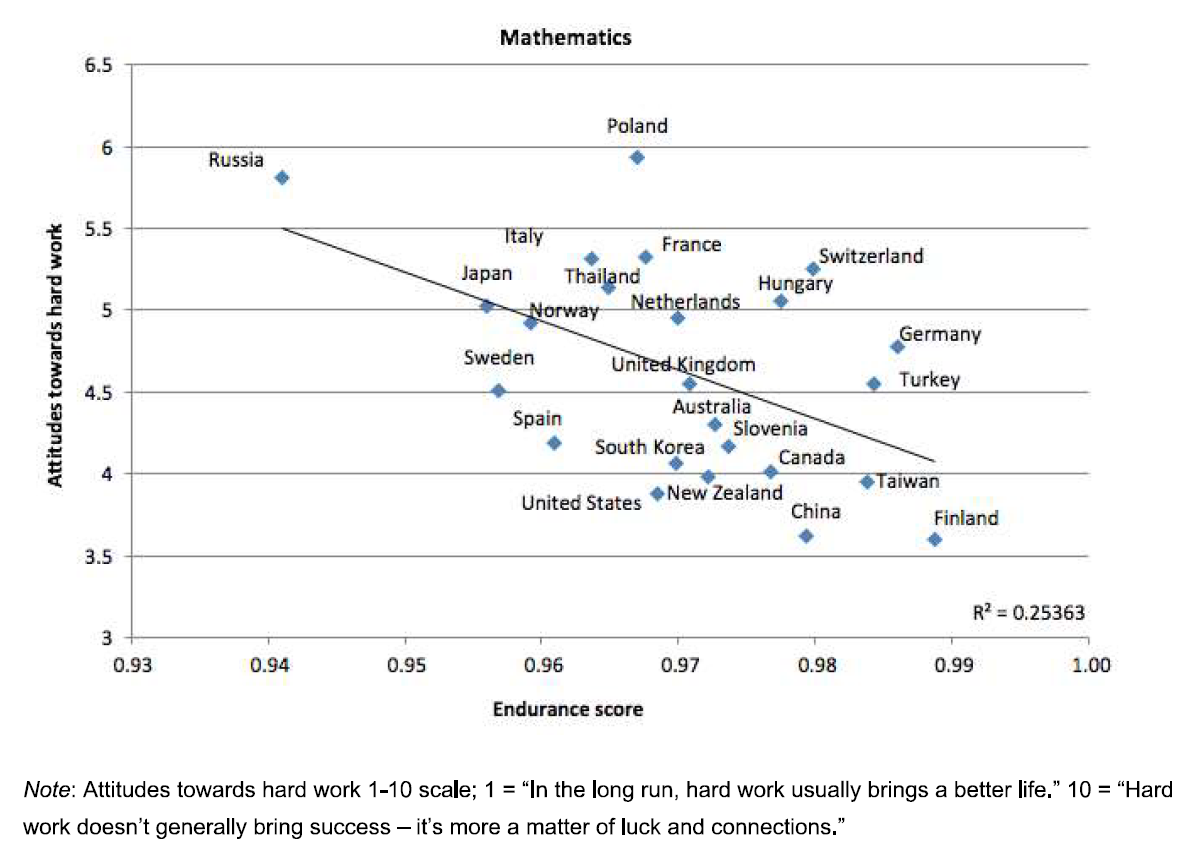

The international tests (e.g. PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS) that are used to look at cross country differences between tracking and non-tracking countries are so-called low stake tests. This means that for the pupils who make the tests there is often nothing at stake. A good example of a high stake tests is the central exit exam that some countries administer at the end of secondary school. These central exit exams often determine whether the pupils obtains his/her degree. For the pupils there is therefore a lot at stake during these exams. The pupils will prepare well and also during the exam the pupils will put in a lot of effort to answer at least as much as possible correct. The low stake international tests have no consequences for the pupil. He/she often does not even receive a grade or other feedback. It is therefore to be expected that he/she is less motivated to perform well.There could be country differences in the extent to which the pupil perform less well. For instance, it is often said that the "work ethic" of Asian countries makes Asian pupils more prone to perform well on any test, even though there are no consequences for the pupil. The figure below shows just that: the correlation between an endurance score (how pupils perform at the beginning and at the end of the test) and attitudes towards hard work (1=positive; 10=negative) of different countries from a summary blog post on this topic (Borgonovi, Hitt, Livingston, Sadoff & Zamarro, 2018).

Figure 4: The relationship between societal attitudes towards hard work and endurance (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Borgonovi, Hitt, Livingston, Sadoff & Zamarro (2018; Figure 2).

Source: Borgonovi, Hitt, Livingston, Sadoff & Zamarro (2018; Figure 2).

There are a number of ways that researcher have used to show these motivation differences by countries. The endurance score used above is one way to show how motivation differences can lead to country score differences. Another way is to pay pupils to perform well and see whether some pupils in some countries go up more than in others. In the already well-motivated countries, the score should be less affected by this extrinsic incentive than in less-motivated countries. Pelin Akyol, Krishna & Wang (2018) use the timed responses in the digital version of the tests to look at non-serious pupils (responding "too" fast). These authors calculate that having more motivated pupils taking the international tests can lead to an increase in the international ranks by 15 places, although Borgonovi, Hitt, Livingston, Sadoff & Zamarro (2018) discuss smaller effects.

This being said, Borgonovi, Hitt, Livingston, Sadoff & Zamarro (2018) urge that this finding does not invalidate the international tests! The tests measures a combination of ability and motivation and both have shown to affect later outcomes. When motivation differences between countries are related to tracking, motivation differences between countries are just one more thing which should be taken into account. Why would motivation differences be related to tracking differences? Pelin Akyol, Krishna & Wang (2018) show that pupils from countries with often high stakes standardized tests are more likely to be non-serious. The authors do not happen to report whether these countries are also more likely to be tracking, but this could be the case.

Anticipation effects

Hanushek & Woessmann (2006) find little evidence of a greater performance gain or loss between 6th grade and 9th grade for tracking countries. However, it could be that the performance in 6th grade is already higher in tracking countries than in non-tracking countries because of the tracking system. This could be due to anticipation effects: When the higher track is the more desirable track, or at least in the mind of pupils and parents, and when pupils know that within a few years they will be selected into tracks based on ability, this could provide motivation to already perform better in school now to increase the chances of reaching the higher track. While pupils in other countries are still more playing than learning, pupils in tracking countries might be more dedicated to their school work. This might leads to pupils performing better at 6th grade tests and might also cause them to have less possibility for gaining later on (so-called ceiling effect). Koerselman (2013) looks at this possible incentive effect by using TIMSS 1995 data in which both 3th and 4th grade pupils were tested. The difference in scores between tracking and non-tracking countries became bigger between those two grades. This gives some indication that incentives effects may indeed play a role in tracking countries.Differences are (partly) intended

So far I have focussed on the main issues with estimating the effect of tracking: It is difficult to separate the effects of tracking from other effects, even when we compare outcomes of the group of countries who track early with outcomes of the group of countries who track later.However, what is often neglected in the tracking literature is that there are other reasons, besides being harmed or helped by tracking, why pupils in early tracking countries might perform different or attain different educational levels from pupils in late tracking countries. Two examples of these are that (1) students in early tracking countries often learn other type of skills, for instance vocational skills, and that (2) the post-secondary education options are very different between early and late tracking countries leading to different final educational degrees. Thus performance differences between pupils between tracking and non-tracking countries might be at least partly intended and this is ignored or overlooked in a lot of the studies into tracking.

Effects on vocational skills

The literature on effects of tracking focusses exclusively on effects on general or academic skills. But countries that track pupils often do so into academic and (pre-)vocational tracks. In the (pre-)vocational tracks pupils learn a trade and less emphasis is on the further development of general skills. For instance, in these tracks less instruction hours are spend on general skills and instead there are instruction hours spend on vocational skills. It would therefore not be surprising if (and even expected that) countries that sort pupils into (pre-)vocational tracks would on average perform worse on general skills tests compared to countries that provide all students with further education into general skills. In a similar vein, countries in which some students attend a vocational track should on average have higher vocational skills compared to countries where no vocational track is available.The problem is that vocational skills are not measured cross nationally. For general skills like reading, mathematics and science in secondary school PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS provide internationally comparable data. But no such measurement exists for vocational skills.

Every two years there are international vocational trade ("World skills") competitions. But every member country sends only a very limited number of pupils which can hardly be called representative for the full pupil population in vocational education. And furthermore, the pupils participating are maximum 22-25 years old and therefore also post-secondary education or even training on the labor market effects the skills of the competitors. Using these data to compare countries on vocational skills obtained in secondary school, would be similar to using the Olympic Games to compare countries on their PE programs. Not a fair comparison. Hopefully in the future secondary school pupils will also be tested on vocational skills to allow full comparison of countries education systems.

Post-secondary options

It is often argued that in tracking countries inequalities are increased since the pupils from the lower tracks cannot enroll in university. It is true that when only part of the pupil population is in the track(s) that gives direct access to university, less pupils are eligible for university and thus less have the option to enroll. However, it could still be that in the end the same type of pupils in both tracking and non-tracking countries decide to go to university and given that this group of pupils is proportionally almost equal in all countries, this could not lead to a lower proportion of pupils going to university.However, in tracking countries there are often more alternatives to university, or at least more respectable alternatives. In Germany, for instance, there has been a recent increase in the proportion of pupils with an university entrance degree to enter into apprentenships instead. Pupils view this as increasing their labor market chances.

Another reason for the difference in university enrolment is that in at least some non-tracking countries there are enormous quality differences between post-secondary institutions. In the United States selective colleges are of much better quality than community colleges and also in the United Kingdom the elite universities of Oxbridge are of much higher quality than the rest. Whether this is the case in all (or at least more) non-tracking countries is hard to say since this data is not readable available. But perhaps the enrolment percentage of secondary school graduates into these elite universities is similar to the enrolment percentage at universities in tracking countries. As a teaser: Out of the 4,140 colleges (or 2,474 4 year colleges) in the United States (a late tracking country) only 157 are in the Times HE ranking of 2018, while all 13 Dutch universities (an early tracking country) are in the top 1,000.

References: pdf

Orginially uploaded on 27-12-2019. On 23-01-2020 a new version was uploaded with minor changes in the references.